Get Easy Health Digest™ in your inbox and don’t miss a thing when you subscribe today. Plus, get the free bonus report, Mother Nature’s Tips, Tricks and Remedies for Cholesterol, Blood Pressure & Blood Sugar as my way of saying welcome to the community!

Constipation: The other intestinal disease you need to take seriously

Many people think constipation is merely an annoyance. Nothing could be further from the truth. Constipation can be the precursor to many chronic diseases — including cancers.

What is a normal bowel movement (BM) pattern?

It is optimal to have 1-3 smooth soft stools daily. So, we can consider anything less as constipation. Constipation increases dramatically with advancing age, especially after age 65. Constipation is much more than just a bothersome symptom.

You might have discovered that having infrequent bowel movements adds to the bad odor of stool. Foul-smelling stool and constipation both are related to a much more serious problem: systemic (total body) inflammation of chronic illnesses. To illustrate this better let’s consider what is in stool that is so bad for you.

What happens when “that stuff” stays in your body too long

Of the solid stool material, 30 percent or more consists of a wide range of bacterial strains. The bacteria are not all dead as traditionally reported. In one stool composition analysis, 49 percent were intact, 19 percent were damaged, and 32 percent were dead. The intact bacteria there create a foul odor from digesting remaining food matter, cellular debris, cholesterol, inorganic minerals and proteins that end up in your large intestine (a.k.a. your colon) and lower portion of your small intestine.

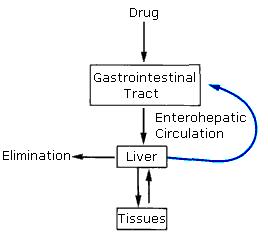

You might wonder, “If the stool exits my body then how can it adversely affect me?” Here’s why: when stool remains in one place, some of the chemicals in it are absorbed back into your bloodstream through the intestinal wall. This is called the entero-hepatic circulation process.

This means that toxic water insoluble wastes in the bile, intended for elimination, can get re-absorbed into the bloodstream. The longer stool sits in the colon, the more these unwanted chemicals get reabsorbed into your body through the called enterohepatic circulation as depicted here:

What kinds of toxic waste can re-enter your bloodstream from your intestinal tract? Consider that you are constantly being exposed to chemicals in your environment that normally must be eliminated daily. These come to you in food, water, air and various commercial products and over time can add to your development of chronic illness. Some of these are:

- Mercury: exposure is almost always from fish. Mercury in the human body is a neurotoxin to your brain and nervous system. Be aware that most people with elevated mercury levels (over the EPA safe level) have no symptoms (yet) or else have subtle, nonspecific symptoms. Studies show an association between coronary artery disease (and heart attacks) and mercury exposures over time. Testing your blood or hair can identify your risk.

- Xenobiotics: these are synthetic and plant compounds in your environment that are not natural to your body, which can disrupt hormone balance. They are widely used in industrial compounds for many applications: personal care products (perfumes, deodorants, soaps, detergents, cleaning supplies), medications, insecticides/herbicides/fungicides, plastics (toys, sunscreens, food containers that get microwaved), paints, building materials, and petrochemicals (gas & diesel fumes). These include PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), BPA (bisphenol A), the insecticides DDT, DDE, endosulfan, kepone, dieldrin, methoxychlor, toxaphene, synthetic estrogens and phthalates (e.g. polyvinyl chloride). Phthalates are universally present in our environment. Interestingly, weight loss corresponds with decreasing phthalates released into the urine over time, suggesting that they get stored in fat tissue. Read about BPA here.

- Beef: hormones are given to beef cows to stimulate weight gain

- Eggs: estrogen is given to chickens to increase egg production

- Milk: growth hormone is given to dairy cows to increase milk production which has estrogenic effects

Let me explain more…

Constipation and leaky gut

One of the major causes of constipation is insufficient dietary fiber. And conversely, insufficient dietary fiber contributes to chronic disease. How? It’s because dietary insoluble fiber is naturally fermented in the colon by healthy bacteria, which produces short-chain fatty acids such as butyric acid and propionic acid. These short-chain fatty acids have been shown to promote colonic homeostasis and health. According to researchers, the short-chain fatty acids (products of gut bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber) regulate the size and function of the colonic T-reg pool (immune cells) and protect against colitis in mice — and most probably in man.

Therefore, anything in the gut that helps destroy the tight junctions of the small intestinal lining creates the condition known as “leaky gut” as I explained in my previous article. In leaky gut, proteins from food that should not normally enter your bloodstream can now leak into your bloodstream and trigger auto-immune inflammation of various types. A similar process could very well occur downstream in the colon, and the longer toxic wastes sit there the more likely they are to find their way back into the bloodstream (entero-hepatic circulation described above).

You can now see how a low fiber diet, unhealthy colonic bacterial strains, and constipation directly contribute to systemic auto-immune inflammation that underlies systemic chronic illness. This is why I see constipation as a contributor to the inflammation of cardiovascular disease, cancer, arthritis, diabetes, skin aging and probably much more. You can see why intestinal health is so important!

Editor’s note: Did you know that when you take your body from acid to alkaline you can boost your energy, lose weight, soothe digestion, avoid illness and achieve wellness? Click here to discover The Alkaline Secret to Ultimate Vitality and revive your life today!

Sources:

- Appl Environ Microbiol. Aug 2005; 71(8): 4679–4689. Full text online at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1183343/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enterohepatic_circulation

- Ronald J. Jandacek, Patrick Tso. Enterohepatic circulation of organochlorine compounds: a site for nutritional intervention. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 18 (2007) 163–167. Full article online at: http://www.eh.uc.edu/growingupfemale/pdfs/P1_PUBS_Jandacek_JNB07.pdf

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enterohepatic_circulation

- Hightower JM, Moore D. “Mercury levels in high-end consumers of fish,” in Environmental Health Perspectives, 111 (4), 2003, pp. 604-608.

- Guallar E, Sanz-Gallardo MI, van’t Veer P, Bode P, Aro A, Gomez-Aracena J, Kark JD, Riemersma RA, Martin-Moreno JM, Kok FJ. Heavy Metals and Myocardial Infarction Study Group. “Mercury, fish oils, and the risk of myocardial infarction,” in New England Journal of Medicine, 347 (22), 2002, pp. 1747-54.

- Dirtu AC, Geens T, Dirinck E, Malarvannan G, Neels H, Van Gaal L, Jorens PG, Covaci A. Phthalate metabolites in obese individuals undergoing weight loss: Urinary levels and estimation of the phthalates daily intake. Environ Int. 2013 Sep;59:344-53.

- Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013 Aug 2;341(6145):569-73.

- Thomas KE, Sapone A, Fasano A, Vogel SN (February 2006). Gliadin stimulation of murine macrophage inflammatory gene expression and intestinal permeability are MyD88-dependent: role of the innate response in Celiac disease. J. Immunol. 176 (4): 2512–21

- Lammers KM, Lu R, Brownley J, et al. (March 2008). “Gliadin Induces an Increase in Intestinal Permeability and Zonulin Release by Binding to the Chemokine Receptor CXCR3”. Gastroenterology 135 (1): 194–204.e3.

- Fasano A (2001) Pathological and therapeutic implications of macromolecule passage through the tight junction. In Tight Junctions. CRC Press, Inc, Boca Raton, pp 697–722.

- Yu QH, Yang Q (2009) Diversity of tight junctions (TJs) between gastrointestinal epithelial cells and their function in maintaining the mucosal barrier. Cell Biol Int 33:78–82.

- Fasano A (2001) Intestinal zonulin: open sesame! Gut 49:159–162.